At a recent antiques fair I bought two small, early Doulton salt glazed, stoneware jugs. They’re a nice example of not spending very much to own some really lovely pieces of antique, ceramic craftsmanship.

If you’ve read many of my other postings you’ll know I’m always on the lookout for early pieces of Doulton ceramics. Whilst I’m fortunate to be able to spend more on rarer items that appeal to me, I’m just as happy to buy modest items that I find along the way. Thus it was that I came across these two small Doulton jugs being sold by a fellow trader at a recent antiques fair.

The jugs are small, being about 85mm (3.4 inches) high. At first glance, they appear to have been produced at the same time with slightly different patterns. However on closer inspection it seems that there were a couple years between them. The earlier hails from the last years of the 19th century whilst the later belongs to the start of the 20th. As such, they span an exciting moment in the history of the company. Let me explain how I get to this.

How to examine ceramics

To begin with a slight digression. It’s become a habit that when I pick up any new piece of ceramic (or glass), after an initial look to admire the overall design, the next stage is to turn it over and look at the base. In doing so you shift the weight (and support!) from the base to the top. You also get to feel the weight properly. I’m very much with the British television antiques personality James Braxston. James often refers to the “Braxton Test” i.e. does it have a good weight to it?

Checking for damage

As you move an item through your hands, either conspicuously or otherwise, you get to check for damage. Often, one can most easily detect chips and cracks by feel. On a vase, the top rim and base are by far the most common places for damage. You should always run your hand around the edges first to check for roughness. If you’re checking glass, do it carefully as sharp edges can leave you needing a plaster!

On jugs, the spout is the most common place for “nibbles” so that gets a finger run over it. However handles needs a visual inspection, and a close one at that. A decent restorer can often hide a reattached handle in the join so it’s hard to see. As a potential buyer should always check carefully, in good light using a torch if necessary.

On the subject of looking for damage, as obvious as it sounds, you must be certain you can see clearly. As you get older, most people start to need some sort of eyesight correction. In my case I use two different pairs of glasses. If you can’t see close up, you really won’t see damage on ceramics. It could end up costing more than a cheap pair of glasses! I always carry a jewellers loupe as well. Using a torch and/or a loupe isn’t impolite. Any sensible buyer will do the same.

Once you’ve satisfied yourself that the item is in good condition (or at least good enough not to just put it back), you should look for maker’s marks. With Doulton ceramics, there’s usually quite a bit to go at. Items without marks are generally worth very much less than those that have them.

Doulton Chine Ware

Both jugs are examples of what’s called Chine Ware. Chine Ware was created by taking the still wet item and pressing lace or fabric into part of the surface. This transfers the fabric’s texture in a way that makes each peice unique. Henry Doulton and John Slater (who worked as the manager of the Doulton factory in Burslem) jointly patented the process. An impressed mark in the base of the jug records this patent (see later).

The ceramicist then added a gilded finish and painted decoration to the textured surface. The rims and handles of both my jugs are glazed more conventionally. Hand painted gold lines continue the gilded theme to complete the designs.

Eyles and Irvine “The Doulton Lambeth Wares” state that Chine Ware was primarily created between 1885 and 1915. At the time, being a new idea, I suspect Chine Ware was very popular. Today, whilst Chine Ware items (primarily vases) are a common sight in auctions and antique shops, they sell for relatively modest sums. This is a shame, especially since the technique appears to be quite complex to apply and can be very appealing. I particularly like the technique on small items such as these jugs or mixed with more conventional glazes on larger items.

A Doulton Slater jug

Looking at my examples in turn, one is clearly earlier than the other. This is easy to tell because the maker’s mark says “Doulton Lambeth England” whereas on the later jug, although it’s not very clear, there is the “Royal Doulton” mark. Edward VII granted a Royal Warrant to the Doulton company at the end of 1901. This would have been a great source of pride for the company. From 1902 onwards the company became Royal Doulton. Ceramics since this date include the crowned lion symbol in the maker’s mark.

Interpreting the base

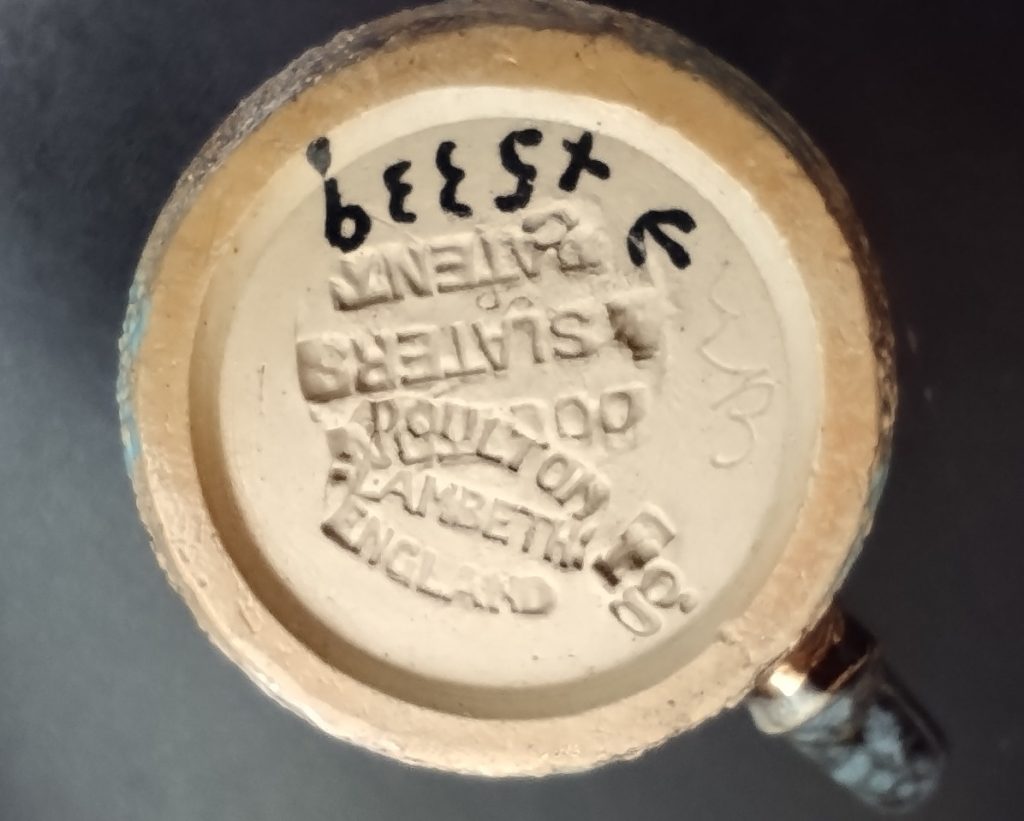

The earlier of the two jugs has several interesting base marks, some more obvious than others. The most obvious impressed ones say “Doulton Slater Patent” and “Doulton Lambeth England”. The Doulton Slater Patent relates to the Chine Ware technique explained above. Clearly at this stage Doulton were still protective about the technique and it was still new enough to be important in marketing to advertise it. Doulton Lambeth England is the maker and as explained sets the date of manufacturing at pre-1902.

The next mark to consider is the inked writing which says “x5339”. This is actually the Doulton design number. I do not know when this was applied. Initially I assumed a previous owner who, having done some research, had written it on. I wonder if it was added during the production process as I have seen several similar examples around the internet? The pattern number was certainly added by hand on Doulton’s bone china porcelain. The design code of x5339 ties the production to between 1897 to 1902. As the jug does not have the Royal Doulton symbol that narrows the upper date range to 1901.

The artists’ marks

Other, less obvious, marks are those of the artists. The hand scribed letters appear (to me at least) to be “WB”. Eyles and Irvine offer two possible suggestions: William Leonard Barron and Winnie Bowstead. Since William Barron apparently left Doulton in 1884 that means, if we can associate the signature with anyone, it must be Winnie Bowstead. Winnie’s mark doesn’t narrow our jug’s production range at all as she worked for 50 years, from 1896 to 1947. It’s not surprising that her mark is a common sight on Doulton ceramics.

The second signature mark appears to be an impressed ‘rg’. Sadly I can not find any reference to these letters. It’s a shame. Even if it was only by name, it would be nice to think the artist was remembered for something that has given pleasure for over a hundred years.

The rim decoration

The final part to consider on the jug is the glaze on the top and handle. I find this type of finish to be the most attractive for Doulton stoneware. It is smooth, glossy and faultless. Here the colours are a bluish, smokey grey and look like dark clouds illuminated by a late evening sunshine. Each colour seems to come from a different depth, giving an almost three dimensional appearance.

A Royal Doulton jug

The second jug is very similar to the first, but it is likely that it was part of a larger production run. Of course, each Chine Ware jug has a unique pattern, as the fabric’s application determines the surface pattern.

Interpreting the base

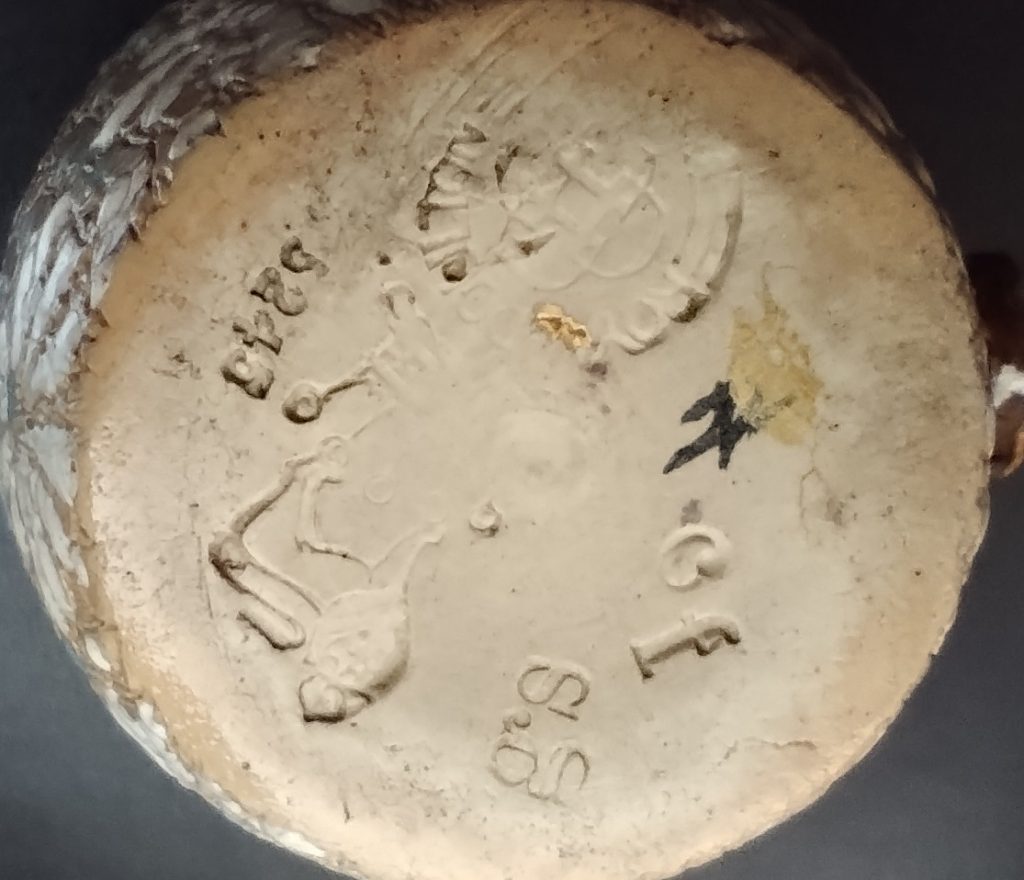

Looking at the base we can see just about make out the crowned lion mark of Royal Doulton. This mark dates the jug to between 1902 and 1914. There is also a design code which unfortunately is rather indistinct. However, if I was to guess it looks to me to be 5245 which would put it in the range 1897 to 1902. The two date ranges would then suggest a date of 1902, although I can image that the design code may have been used for sometime after the year it was introduced.

The artists’ marks

Two artists have left marks of “cf” and “gs”. Unfortunately Eyles and Irvine list neither, leaving their identities lost to history. Most assistant artists seemed to have used stamped letters rather than hand-written initials. As such, I guess this jug was only worked on by assistants. As we saw with Winnie Bowstead however some assistant artists worked for decades at Doulton and so their individual contributions could be very significant.

The rim decoration

The top of the jug is attractively decorated with a repeated, raised design picked out in white over a blue ground. As you move the jug around, the raised pattern catches the light differently . It’s surprising how much of a difference this makes compared to a smooth glaze with a printed design underneath.

The search continues: other similar Doulton jugs

Since I bought these jugs I have come across several other examples. They are never very expensive so a small collection wouldn’t cost very much and, as genuine antiques, they would be a nice subject to collect.