Deciding on the perfect selling price for an item is difficult in any business. With art and antiques given the range of sources, cost and the difficulty of getting more of the same, it can be especially problematical. You can make life easier for yourself though by keeping good records.

Turning in a profit

Most businesses try to make a profit. Selling art and antiques is no different even if the original motivation is often as much about an interest in the objects as it is about the money. Getting to see, and even owning, interesting and beautiful objects is inherent with the business but making a profit needs a lot of work.

Sourcing issues

The key to a profit is being able to set the selling price at the right level. This sounds obvious and easy but when you’re buying and selling difficult to source, rare or one off pieces you can’t just sell an item and simply buy a replacement. Sell an item too cheaply and you’ve lost potential profit on something you may never see the like of again. Set the price too high and it will stay in stock for so long you’ll never want to see it again.

A business selling new items can expect to make a sale and then contact the supplier for another shipment. This usually comes with a fixed delivery time and a known cost. You can display items that are not for sale, knowing that if a customer is interested, you can quickly supply one. This just isn’t the case with antiques.

Sourcing art and antiques is a slow and time consuming process. In truth it’s usually a thoroughly enjoyable, slow and time consuming process, but it’s a slow and time consuming process nonetheless. You must factor the cost of your time and effort into the selling price of every item you have if you’re trying to make money.Regardless of how you account for your time, on a day long trip to an antiques fair you will rack up some very tangible costs such as fuel and an entry fee. These have to be covered by the profits of whatever you buy and it’s nice to add some element for your time.

Time is money, but it’s not all about money

The cost of your time is very subjective. Putting a value on it depends on why you’re trading. Trading is a hobby for us. This is also true for the majority of people selling at an antiques fair or indeed from antiques shops. For us, it’s not a hobby we can afford to lose money on but thankfully it’s not about paying the bills or putting food on the table. We’d be very hungry if it was.

At the other extreme, some people are content to trade and even though they lose money. One trader explained that it was cheaper than joining a golf club and it kept him out and about. The Yorkshireman in me shuddered at the thought of the effort involved and still losing money but I understand the guy’s point.

There are very few people who trade full time in art and antiques and have no other source of income. Quite simply, there isn’t that much money in the business. If you have free time it is however a great way to generate a supplementary income and for people on a pension it provides an interest and a reason to keep very active. If you look around the traders at an antiques fair, if you’re under 50 you’ll be in the minority.

Pricing – where to start

So you’ve bought a single item that you think you can resell at a profit. How do you go about deciding on a price. Today there are two obvious starting points. Firstly of course, what did you pay for it?

In general the cheaper the object the higher the profit margin by percentage. For example, at the cheapest end of things, there’s no point buying an item for £1 and selling it for £2. That’s a 100% percentage profit margin but something like a plate is going to take up a fair chunk of display space. Unless you have a lot of display space to fill, you need to receive about £5 for an item you paid a £1 for.

A £5 selling price for a £1 cost is a brilliant markup but when you get to paying £200 for vase you’re unlikely to get the make percentage. That would require a selling price of £1000. Few people at an antiques fair ever get an £800 profit from a £1000 sale.

So as the cost of an item rises, you probably have to reduce the profit margin. Selling a vase that cost you £700 for £1000 is less than 50% markup but it’s still £300 profit. It takes a lot of effort to make £300 from £5 sales even if each of those items only cost you £1.

The trade off is that the vase that delivers a £300 profit will probably take a while to sell, but you should be able to sell lots of £5 items in the meantime. The vase however may have only taken up as much display space and transportation effort as a couple of £5 items. Everything has to earn its place in your display and you need to be mindful of that as a cost.

So you know what you want to get for your item, but what chance have you got of achieving it and could you even get a bit more? The second place to check for a price is of course the Internet.

The Internet, and in particular the Web, has changed so much of our every day life it’s hard sometimes to remember what it was like before its widespread use. A few traders prohibit the use of tools like Google Lens on their items. Whilst I understand that, to be honest I think it’s a waste of time.

Along with the rest of us, traders use Web searches to find a guide price and other information for items they aren’t wholly familiar with. You can’t expect a customer not to.

As a trader, the trick is to price your stock close to the best Internet price available. If a customer does a Web search they will be encouraged to find your prices are as good as they can get. You can probably get away with a small percentage on top of the cheapest internet price and still not put a buyer off. Most people like to see an item before they buy it and with wear and tear on old items, paying a small premium for the example you’re holding and have inspected is very compelling.

Buying in bulk

Sometimes you don’t buy stock one item at a time. Sometimes stock comes in multiples, sometimes quite large multiples. We like buying bulk lots at auction, especially mixed lots, as these often contain one or two items that pay for the whole lot leaving the cost of the remaining items as effectively nothing.

It’s a good day when you find yourself selling items that cost you nothing, other than their display and transportation costs.

Contrary to what you might believe, or hope, it’s very unusual to find really high value items sold cheaply in mixed lots at auction. It does happen but it tends to make the news when it does, it’s that rare. Finding single items that pay for the whole lot is more common though and I’ve written about this previously. These are good purchases and it makes pricing the rest of the lot much easier.

Allowing for discounts?

When we sell items from the shops, it’s surprising how few people even think about asking for a discount. British devotees of “Bargain Hunt” and customers from a few other cultures tend to be very clued up and will try to haggle, but most don’t. I don’t know if this is a cultural thing or a language limitation but it certainly adds a bit to our profits. The shops we sell from do have hard and fast rules on discounts however and in truth it’s very rare to lose a sale because you won’t lower your price beyond those limits.

At fairs, a discount is expected on pretty well anything above about £10. This makes setting a selling price more difficult as all the items need labeling for the shops and it’s impractical to relabel for a fair. In the end, it’s safest to assume that any item you sell will have a discount of at least 10% applied and this usually means you add 10% to the label price. The game is a frustrating one, but you need to play along.

Keeping track of your successes (and failures)

As you buy and (hopefully) sell an item you generally have to keep track of your cash flow, if for no other reason than most of us will have to complete some sort of tax return. In the UK we are lucky. HMRC defines the rules clearly. It’s fair to assume every trader in an antiques shop or fair will be operating well above the minimum turnover level for HMRC to take an interest. Indeed, even if you’re below the threshold you should be keeping track of your turnover so you can prove that you are indeed below.

Different traders track their stock at different levels of granularity. After a working life in data management it’s probably not a surprise that we keep very close records. If you can manage it there’s a good case for doing so. It is time consuming but it allows for reporting that is both interesting and commercially valuable.

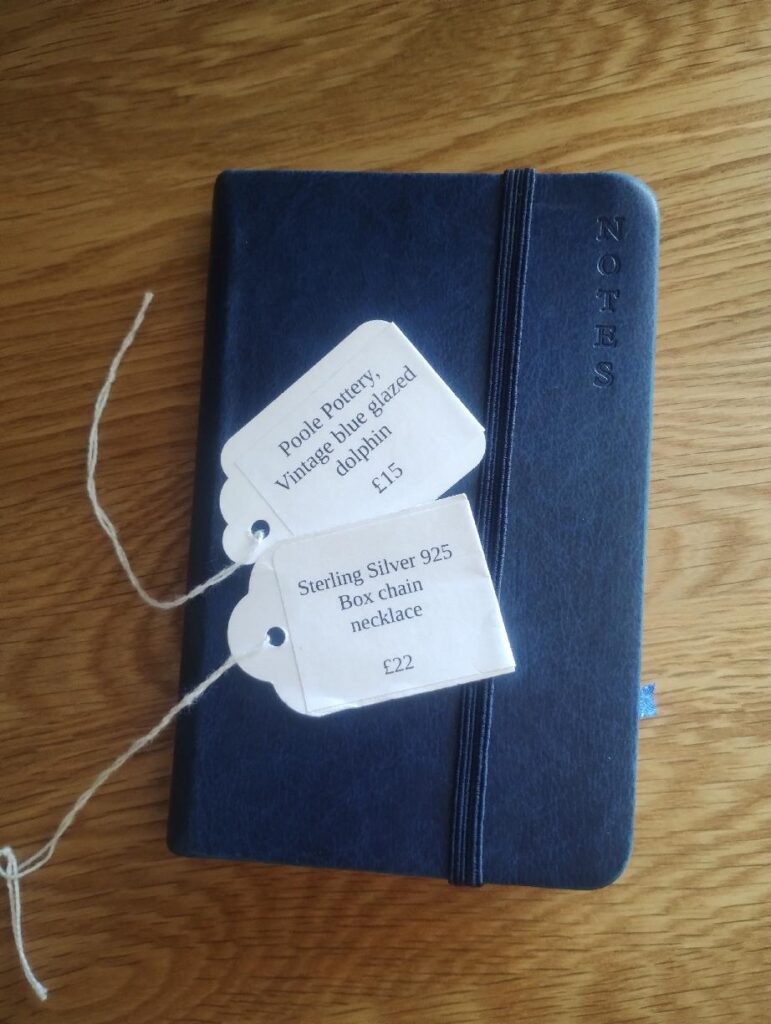

Some of this was covered in a previous article where I gave the low down on traders’ labels and what to look out for. However, for completeness, this is the information we collect for each item and why:

- Date of purchase – First and foremost this tracks which stock was bought in which tax year, and is thus a cost in that year. It also allows you to track what stock has been with you a long time. For us, anything over about three years is probably getting towards discount time although I know some traders who are happy to try stock for five years. They must get very bored of the items.

- Place of purchase – Partly just for interest but when tied with Date of Purchase this allows us to see how well we’re doing selling down all the items we purchased on one day at the same place. Reporting on this shows places we bought well at in the past and those that have been a disappointment.

- Cost of Purchase – You should have a record of this for every item you buy unless you’re buying large quantities of very low cost items. Even then, you need to note the purchase as this is a cost for tax purposes. Combined with sold price, cost of purchase allows us to see how much profit we made at sale. If an item has been with us for a while it’s also useful when we’re wanting to sell something at a larger than usual discount so we can see how far can we go and still at least break even.

The total of Cost of Purchase for all your unsold stock is of course a number worth monitoring in itself. We probably watch this number as closely as any. We have a fairly hard limit for it so we don’t just keep buying stock endlessly. - Ticket Price – This is a useful value to note. In our case we can generate our item labels fairly automatically so the ticket price comes straight from the system. Of course there’s often a discount but totaling the Ticket Price for all unsold items shows you the maximum likely amount you would get from selling all your stock. We actually report on 80% of this figure to get an idea of what’s more realistic as this allows for a good discount and other costs we incur along the way.

- Date of Sale – This tracks when an item was sold. It has lots of uses, such as what you sold in a given time period (typically month/year) but also how long you had the item in stock. If you’re inspired to replace an item it’s good to be reminded how long it was with you. Sometimes, trying again might not be a good idea. This date is not used for is tax reporting – that’s the next date.

- Date of Payment – If you’re selling at a fair then you get your money straight away. In shops getting paid for sales is generally at period end, whenever that is. This is important around tax year end when you may sell an item but for tax purposes you don’t get the money until next tax year.

- Sold Location – Combined with Date of Sale, this allows you to report on what was sold on a particular date and location. This is really useful when we’re planning which fairs we want to sell at in the coming few months. Being able to look back at the performance of a particular fair in a particular month tends to be our guide as to what we’ll sign up to.

- Sale Price – The best bit of information in your system, how much did you get for an item. Combined with purchase price this shows your profit, before any additional costs. It’s one of the fundamental numbers you’ll need for tax reporting.

How to keep your records?

There’s probably a (much) longer posting on this subject to be written at some time, so for now I’ll keep it short.

Whatever information you use for tracking, it needs to be something you’re comfortable with. Many traders simply use notebooks. This makes me shudder. Losing or damaging notebooks is very easy. and with no backup available you risk losing so much so easily.

A simple spreadsheet goes a long way to solving most of the issues with notebooks. You can take backups and since most of us use a smart phone you can email yourself a report of your stock that you can take with you wherever you go (a pdf export is usually a simple thing to generate). Reporting from a spreadsheet is as simple or sophisticated as you can manage. Indeed if you’re wanting to improve your skills with spreadsheets it gives you a reason to learn. A spreadsheet was how we started and it fulfilled most of our needs.

If you fancy learning, or are capable of, a bit of programming then the sky is the limit. This is where we ended up, with a custom written application. We probably didn’t need to go this far but the reporting it provides certainly gives us advantages over any other trader we’ve met.