Moorcroft ceramics were the first ceramics that I started to collect. I loved it then and I still do. That’s not to say I cherish all their designs, but when all the elements are right I don’t think there’s much to beat it. I still buy (and sell) more Moorcroft ceramics than any other maker and I never pass a piece by without looking at it.

At any one time I own a fair number of examples and have a good few that are part of my own collection. These are definitely not for sale. The pieces I own vary in size, age and style, ranging from a vase bought at auction made in the 1920s, to a Kakapo plate made in 2010, bought new from the Moorcroft visitor centre in 2018.

“Condition is key”, or is it?

When buying second-hand ceramics, you quickly learn the phrase “condition is key”. Put simply, if ceramics are damaged their value drops hugely. For pieces under about a hundred years old, there is generally an expectation of near perfect condition. Only for very rare or special pieces is visible damage acceptable to collectors.

Collectors of Moorcroft however soon learn that their ceramics have an almost inevitable tendency to develop crazing that would render many other manufacturers pieces if not valueless, at least, much less desirable. For obvious reasons, this is something that interests me greatly, especially when it comes to valuing pieces for purchase and resale.

As I started trying to understand what is going on, I gradually learned that there’s no definitive answer as to why Moorcoft ceramics craze and or indeed why it seems acceptable to collectors. As I started to ask around people I thought might be able to explain what’s going on, I found I got some strange, some rather vague and sometimes some rather defensive responses. So, let me explain how far I’ve got. It sometimes feels like a family secret that is known to all but shouldn’t be discussed in public, if at all.

What is crazing?

Let’s start at the beginning with my understanding of what crazing is. Put simply crazing is a crack in the glaze applied to the outer surface of ceramics. Glaze is basically one, or more usually a number of, very thin layers added to the surface which after firing becomes a form of glass. Each layer of glaze is usually fired separately so the finished piece will have been in a kiln multiple times before it is finished. Each glaze includes additives which give different effects when fired, not least of which is colour.

As you will know from experience glass is both hard but also very brittle. Basically the body of the pottery provides the strength whilst the glaze provides a hard, glossy, waterproof, inert and beautiful coating.

The hard, inflexibility of glaze means it has almost no ability to absorb energy and is thus very brittle. When exposed to stress there is nowhere for the energy to dissipate and as a result it cracks.

It’s not to be advised but you can feel the same effect throwing a ball. Try throwing a cricket ball really hard and then do the same with a much lighter ball, such as you might throw for a dog to chase. With the heavier ball all the energy transfers to the ball. With the lighter ball it the energy transfer is less efficient leaving you with excess energy in your shoulder. This can really hurt, and in an extreme case you throw your shoulder joint out.

Crazing or cracking?

Crazing in ceramics is not usually considered to be the same as a crack. A crack is more serious as it extends into the clay body of the item and may lead to it ending up in several pieces. Only in something made entirely of glass does a craze and crack become the same thing. In this case a craze simply extends through the object, becomes a crack, resulting in a pile of glass shards.

On a piece of ceramic, crazing stops at the pottery layer and goes no further and doesn’t usually threaten the integrity of the item, although it may disfigure it. If you’re not sure how deep crazing goes in a piece, be very careful to study it. Making the wrong call can be very disappointing.

Crazing on Moorcroft ceramics

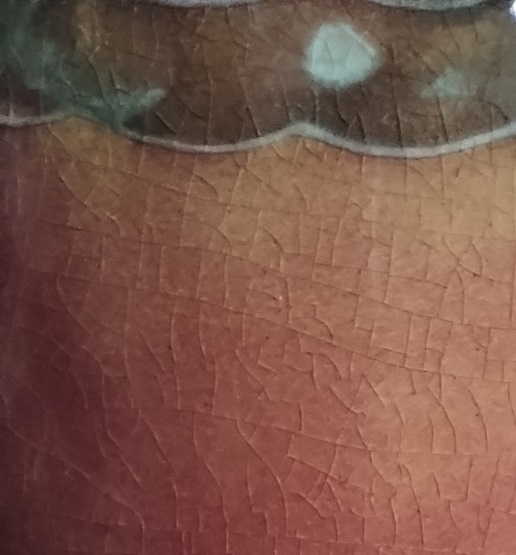

If you take a look at Moorcroft ceramics you will see that whilst most older pieces are crazed, not all pieces seem to craze in the same way. I’m not aware of any research on this but from my experience I think there are broadly two types of crazing, depending on the age of the piece. Older pieces craze a lot, in a tight mesh-like pattern in a uniform but random way. To my eyes there are fewer long smooth craze lines. The crazing also appears to be less obvious as if the glaze is thinner.

More modern pieces tend to craze in longer straighter lines and where a “mesh” forms the uncrazed areas are larger. I also think the crazing appears to be deeper.

I don’t believe this difference is crazing is simply related to the age of the piece. However I would concede that to be sure you’d need to artificially stress pieces of different ages to see what happens. I’m afraid my budget doesn’t run to that!

My feeling is that given another fifty years, a piece from 1990 will not develop the same crazing as a piece from 1940. The pattern of crazing in more modern pieces look to me as if it could develop into the fine mesh like crazing of older piece. At most it would have a larger mesh size or more likely simply longer fairly straight lines.

The reason for the difference in crazing patterns is almost certainly that, over time, Moorcroft have changed the makeup of the glazes that are used. I’ve been told by a couple of people (including a Moorcroft sales person at the Malvern Autumn Show) that the earlier pieces shouldn’t be handled because of some of the chemicals included in the glazes. This is backed up by a story told to me of one of William Moorcroft’s daughters recalling her days as a child visiting the factory and the terrible fumes around the kilns when some of the firing was taking place.

I imagine that, amongst other things, lead was involved. Lead has long been an addition to glass as it helps to lengthen the working time. I learn from the Internet that prior to regulation in 1969, lead crystal could contain up to 36% lead. I have no idea if arsenic was ever used by Moorcroft but it wouldn’t be a surprise as it too was a regular addition to glass (it helped remove gas bubbles).

Flambe glaze, a special case?

Some earlier Moorcroft work was given a “flambe” glaze. This adds a reddish hue to the finished product and is usually quite sought after. I’ve been told by a couple of dealers that the flambe pieces are sometimes less prone to crazing. This is rather ironic because the flambe glaze was often applied to pieces where the initial firings hadn’t been completely successful and the flambe glaze masked the disappointing initial glaze colours.

My own experience suggest that flambe does craze, but the glaze is darker and so the crazing is less obvious, or possibly I’ve just not had chance to see enough flambe pieces. I do wonder what was in it as Moorcroft flambe glazed items have a been mentioned to me as pieces you shouldn’t handle more than you have to.

When does crazing start?

When considering Moorcroft it’s worth dividing history into three phases:

- Pre-1950: largely the era of William Moorcroft

- 1950 to mid-1980: largely the era of Walter Moorcroft

- Mid-1980 to today: The Richard Dennis and later era

Pieces in the pre-1950s era will almost certainly be crazed, with fine mesh-like crazing. This if often hard to see and you may need bright torch shining at an oblique angle to see the lines. This is particularly true of darker colours. Even pieces in the Moorcroft museum show this sort of crazing and it can probably be assumed they have looked after their own work.

In the 1950 to mid-1980 era most pieces will show some crazing although if you’re lucky you can find them without. When crazing occurs it tends to be the fine mesh crazing and again isn’t too obtrusive. We have a ginger jar we believe dates from towards the end of this era in perfect condition. We were lucky and were able to purchase it at a reasonable price. I have seen other similar ginger jars from the same era that show significant crazing.

From the start of the Richard Dennis era, uncrazed pieces start to become more common but it’s very hit and miss. If you’re buying a new piece it should, of course, be perfect. That however doesn’t mean it was made recently as some dealers hold stock for decades. On a recent visit the wonderful Sissions Gallery in Helmsley I admired a Finches pattern lamp. That design was not used after the designer Sally Tuffin left in 1992, which means it’s at least 31 years old (selling high end Moorcroft is a long game!).

One of my prized pieces is a very large squat vase with the Finches design. It was once owned by the publisher Felix Dennis (no relation to Richard Dennis). Felix obviously knew how to look after ceramics (or had staff who did) as it is in perfect condition. I’ve seen two, ostensibly identical, examples which showed significant crazing.

Buying second-hand Moorcroft of this age requires a very close examination. Be warned that some auction houses do not consider crazing to be worthy of mention in condition reports. It’s also very difficult to see in the photographs published in online catalogs. You really need to see pieces close up, in person to be sure you know what the true condition is.

Why do Moorcroft ceramics craze and is it inevitable?

In this posting I have, so far, have rather accepted that crazing just happens “naturally” in Moorcroft and that at different ages the crazing is generally different. We now need to ask is this just inevitable? I’m not a ceramicist so these comments are just considered opinions based on a lot of observation and a number of conversations with people who I believe to be very knowledgeable.

The short answer is that this is a very difficult question. It also seems to be a question that people whose income depends on the public continuing to buy Moorcroft pottery rather skirt around.

Firstly, it should be recognised that not all glazed ceramics craze as they get older, although one Moorcroft sales person tried to tell me very vigorously that they did. Maybe I should take along a 1920s era Royal Copenhagen vase as evidence! If you’re not familiar with Royal Copenhagen ceramics look out for them. The early 20th century art pottery is gorgeous and looks as good as the day it came out of the kiln. It can be hard to grasp just how old pieces are.

As I noted above, glaze is a glass-like coating that is very thin. It is formed at very high temperatures in a kiln and is then cooled slowly back to room temperature (typically 12 hours or more). The rate of cooling causes different effects in the glaze but the basic idea is that slow cooling is required to minimise stresses in the pottery and the glaze. Even pottery and glass exhibit some thermal expansion so you need everything to cool and contract at a very slow rate.

Modern kilns are very different to the kilns of the 1920s. The control available is very much greater and so it’s reasonable to assume that firing ceramics today is a very much more controlled experience.

Even with modern, computer controlled kilns where the temperature is tightly controlled throughout the firing cycle, things don’t always go to plan. Items crack in kilns but at least in this situation you know it has happened. More insidious is a piece of work that is stressed internally but not so much that any damage is visible to start with but it’s just waiting for that first additional external stress to start crazing. It would be interesting to know if Moorcroft have to throw away many pieces that come out of the kiln with crazing.

One thing you can be sure of, if you buy a piece of Moorcroft ceramics from new, it should be uncrazed. What happens next is probably up to you, at least for the next thirty years at least. After that sort of time, it may be impossible to predict. There certainly seems to be a tendency for crazing in Moorcroft ceramics that is almost unique to their work.

It is interesting to note that Dennis Chinaworks’ products have a very similar issue. Dennis Chinaworks is, of course, owned by Richard Dennis and Sally Tuffin who were involved in rescuing Moorcroft from ruin in the late 1980s. Their produce is very similar to Moorcroft and I would assume they use similar glazes and firing processes.

Avoiding triggering crazing?

So, how do you avoid triggering crazing on your perfect piece of Moorcroft pottery? The opinions of those I have asked vary. It seems that either no one knows for certain what starts crazing but there are several things that will do it. If we try to assume that crazing can be avoided (at least for decades), we’re looking for external factors. The most likely seem to be as follows:

Physical impact. We’ve probably all knocked a drinking glass against a metal tap and been left with glass shards in the sink. So, being careful is a really good start. Just a gentle tap against another piece of ceramic or just putting an item down a little harshly when dusting can be enough. For dealers, the most obvious time is when packing, unpacking or transporting pieces to a show. This is why you should always be really careful when buying at a fair or auction. Lighting at fairs is often not great so use a powerful torch (mobile phones are brilliant for this) to inspect pieces before purchasing.

A large temperature difference across a piece. This is possibly less obvious but a vase with a dark area exposed to direct sunlight on one side will absorb much more energy in the dark area than the surrounding lighter areas. At the same time the areas not exposed to the direct light will heat and expand very little. Glaze is very brittle so the you only need a tiny amount of uneven heat expansion and you’re in trouble. It might not happen on day one but over a period of months or years this can cause problems.

As with direct sunlight, artificial heating such as a radiator can have the same effect. A vase over a radiator is certainly going to heat up unevenly. For this reason you should never display Moorcroft ceramics over a heat source or in direct sunlight.

I have heard the suggestion that thermal shock can be an issue. This is where a piece is taken from a cold place to a warm place very quickly. If the temperature is significant then the surface will warm up more quickly than the body. The most obvious would be if you were to take a piece from the outside in winter into warm house.

One possible scenario is if you get a piece delivered and it has been in an unheated delivery van for a few hours. If this happens to you, be patient and leave the package in your house for a few hours before opening it. The packaging will act as insulation allowing the item to warm up gently. (In case you didn’t know, this is really good advice if you buy electronics over the internet and get them delivered on a very cold day. Most electronics are designed to operate at room temperature and will have a minimum of about 4C. The back of a van on a frosty day may well be below that, so let them warm up first).

Does crazing matter?

After all I’ve written we come to the question of does it matter? Does “condition is key” include crazing or not?

Crazing is certainly a visible change in state from the how the item looked when it was purchased. It is however not likely to threaten the integrity of the piece in the way a crack would. I’ll come off the fence here and say that to my mind it is a form of damage and as such it is regrettable and should be avoided if at all possible.

I heard a very vigorous defence of crazing from a Moorcroft sales person (for the sake of openness, at the Malvern Autumn Show, 2023). Their view was that collectors like crazing because it is impossible to repair a piece and fake the crazing. I have to say I think this is a pretty weak argument and is rather clutching at straws. However, the second hand market for Moorcroft is very active, albeit that second hand pieces sell for as little as 25% of the new price, often regardless of crazing.

So, as a collector or buyer, should you worry about crazing? I’ve stated my position and I think you should do all you can to reduce the risk of crazing in any piece that is currently uncrazed. As someone who frequently buys and sells Moorcroft I try my best not to trade in pieces newer than about 1970 if they are crazed. This is a fairly pragmatic stance because it becomes almost impossible to obtain pieces older than that with no crazing. Many of the most desirable pieces are at least that old. I wouldn’t knowingly touch pieces newer than about 1990 with crazing.

I’ve noticed that the lighter the colour the more the crazing,or is it because it’s more visible?

That’s a very good observation, about which definitely I’d agree. I think there could be a couple of factors involved. Crazing is certainly more visible where there is a lighter background colour. The crazing tends to cause a slight shadow within the glaze which naturally shows up more over a paler colour. Another aspect of this is that the pale cream background, so common in modern Moorcroft, was relatively unusual prior to about 1980. I think this means that there is a tendency to see the crazing more visibly in modern pieces.