For the first time in far too long I had the chance to spend a few hours in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Given my recently found interest in 18th and 19th century British art ceramics I decided I’d see what the museum had to offer. It turned out to be better than I imagined.

First visit for seven years

A combination of the COVID pandemic, a lack of time and an inability to get organised meant that I’d not been to London for seven years. This was remedied recently and I took the opportunity to visit the Victoria and Albert Museum. I’ve been a couple of times before but those visits predate my interest in ceramics. Without any particular target I’d largely just wandered through to see what I found.

The V&A is huge. You can easily get lost and distracted by the wonders on display. Being August, I knew the other mega-museums in London would be rammed with visitors, but the V&A retains a more rarefied atmosphere. In general school age children prefer visiting an animatronic T-Rex than going to see a 200 year old pot. However, whatever your age, if you’ve not seen the animatronic T-Rex in the Natural History Museum, you should go there first. It’s one of the coolest and probably the most unsettling thing I’ve seen in a museum.

Focus or wander

Walking into the V&A you’ve really got two options. Set off and see what distracts you or make a blinkered dash for the galleries you want to see. In the past, like most people I’ve done the former. I can tell you that the Chinese furniture is amazing and the original drawings of Winnie-the-Pooh are as endearing as you’d hope.

This time I was determined to be more focused. I despair of my ageing legs and their inability to hold me up for eight hours without a rest. These days I find about three hours of standing still is about all they can handle, so I have to spend my time wisely. I entered the museum shortly after opening time. After a quick check of the floor plan I headed to the third floor. I barely saw another visitor for two hours. Quite simply unless you specifically head up the stairs you probably won’t see above the first floor before your legs give out or it’s time to leave.

The third floor

Ascending to the third floor I headed for the British ceramics to 1900 section. My main aim was to see what early Doulton, Martin Brothers and Wedgwood the museum curators had on display.

Of Wedgwood I didn’t actually expect there to be a great deal as I’ve twice visited the V&A Wedgwood Collection at the Wedgwood factory in Stoke. I’ve written about Wedgwood Jasperware before and how I feel it’s very under appreciated today. The Wedgwood museum in Stoke alone takes me three hours to go around. It’s a place of utter joy and fascination for me. However, as it turns out, the V&A has far more Wedgwood than I could have imagined as there is another museum’s worth in London.

I’ve seen collections of Martin Brothers and early Doulton stoneware in a number of provincial museums. Typically several pieces are grouped together with a little bit of information about their history. I know the Birmingham City Art Gallery and the Ashmolean in Oxford have very good displays. Both are worth taking time to see if you’re near by. However they don’t extend beyond a single display case and there’s not a great deal of context or information. In my naivety I think I probably expected something similar in the V&A but maybe on a bigger scale.

It turns out the V&A takes a different approach to the main part of their displays. Rather than simply group all the pieces they have by a manufacturer they illustrate aspects of history through displays of objects. There’s no way to cover all of what’s in the galleries, or indeed even the delights I stopped to look at, but in the hope it might inspire others to ascend the stairs to the third floor, let me share with you some of the displays I particularly liked.

“Vasemania”

Josiah Wedgwood coined the expression “Vasemania” in the 18th century to describe the (very lucrative!) enthusiasm for vases in Britain and it’s colonies.

The V&A’s choice of vases to illustrate “Vasemania”. I image the curator had a very enjoyable time picking the exhibits for this one

Excitement around the excavations at Pompeii that were taking place at the time were key to this. William Hamilton, a British collector of antiquities, who obtained a number of vases from Pompeii collaborated Josiah Wedgwood. The arrangement being that Wedgwood provided experts to restore Hamilton’s collection and in return Wedgwood was able to copy the designs for his pottery.

There is an excellent example of how closely Wedgwood attempted to copy antiquarian vases in the V&A with two vases displayed side by side, one ancient and one from the 18th century. Tristram Hunt in his excellent biography of Josiah Wedgwood “The Radical Potter” (a Christmas present to me last year) describes this in some detail. Seeing the display really brought the point to life.

The influence of the classical world on ceramics was enormous and outlasted both men by a couple of centuries, indeed it continues to this day. If you look at even the most humble piece of Wedgwood Jasperware the chances are the designs look as if they could have been taken from a vase in Pompeii – indeed they might have been. The only significant difference is that Wedgwood’s figures generally have more clothes on!

Ceramic motif moulds

Sometimes the smallest displays can really strike a chord when you walk around a museum if you have a bit of background interest. The display of moulds shows a number of moulds used to create ceramic ornamentation.

Whilst the large moulds on display would have been used for architectural pieces, the idea can be scaled down for smaller work.

All of the patterns on Wedgwood Jasperware are made in the same way, just on a smaller scale. In later times, Doulton used similar techniques to decorate many of their stoneware vases between about 1870 and 1930.

The Portland Vase

Sitting proudly, if quietly, in a cabinet is a copy of the Portland Vase.

Most items in a museum are pretty hard to put a value on, but first editions of Wedgwood’s Portland Vase come up for sale from time to time. As I write I see that you can expect to pay somewhere over £100k for one. As you’d expect from the V&A, their example looks perfect. It’s the first time I’ve actually seen one in the flesh. It is superb.

The Portland vase is a copy of a 1st century BC cameo glass vase. If you are interested, details of the vase can be found on the internet. History records that it took Josiah Wedgwood five years to create a perfect copy in Jasperware. Wedgwood considered it to be his greatest ceramic achievement. When the vase was first put on show, 1900 tickets were sold for the original exhibition. Can you imagine that today?

Along the way, Wedgwood pushed back the boundaries of what could be achieved with ceramics. I guess many of the later designs in Jasperware probably owe a great deal to Wedgwood’s obsession with creating the Portland Vase. Although no price is quoted, the vase remains available, on request. One word of caution though is that I have several versions of varying quality. If you see a Wedgwood Portland Vase advertised cheaply it will be one of the lesser copies.

“Egytptomania”

Around 1800 Europe began it’s obsession with Egypt. This was the era of Napoleon’s military campaigns in Egypt and the subsequent competition, especially between Britain and France, to obtain the best, portable (and not so portable) antiquities. The Rosetta Stone is the most famous example. Found in 1799 by Napoleon’s soldiers, it was taken by the British following Napoleon’s defeat. It’s now a prized exhibit in the British Museum, although as with many such items the Egyptian authorities would like it back. I guess that few people visit the V&A for their Egyptian collection. It’s a pity because the museum has some excellent artifacts that illustrate how much tastes in Britain were influenced by the excitement.

Of course, the interest in Egypt has never gone away and it probably never will. I’m lucky enough to have been to Egypt three times. If you ever wonder is it really as wondrous as it seems on television, I would say that you can’t begin to comprehend the place is until you’ve been in person.

Late 19th century art pottery

If I’m asked to describe my main interest in collecting I’d probably say it relates to late 19th century, early 20th century British art pottery. This covers the era when Doulton pretty well invented the idea of British art pottery and the explosion of creativity from several now famous workshops mostly in the Lambeth area of London. I was delighted that the V&A has some excellent examples of Doulton, C. H. Brannam, Ruskin, Moorcroft and Martin Brothers works to illustrate this era.

The collection of C. H. Brannam (a Devon potter) was particularly good to see as it’s a rather uncommon to see good pieces by him.

I stopping bidding too early on a lovely piece of his work that came up for sale at a local auction recently. Not sure what I was thinking of. Seeing examples in the V&A just helps to validate how good Brannam ceramics are and how much better known they deserve to be.

And then there’s the fourth floor

For a ceramics enthusiast, the fourth floor at the V&A is overwhelming. It’s sort of a store room, but with everything stored in glass fronted, glass shelved racks. The racks are way too high to see items on the top shelves (six shelves in total) but you can get an idea of how much the museum has to offer. Of course much of the collection is online. If you’re able to visit you can apply to see any items close up but for a casual visitor it’s really the scale of the display that astonishes.

For me, thankfully, there were a good number of very choice displays at or below head height which meant I got to see more work by Hannah Barlow (for Doulton) and the Martin Brothers than I’ve ever seen anywhere.

There was also, as I’d come to expect now, even more stunning pieces of Wedgwood Jasperware.

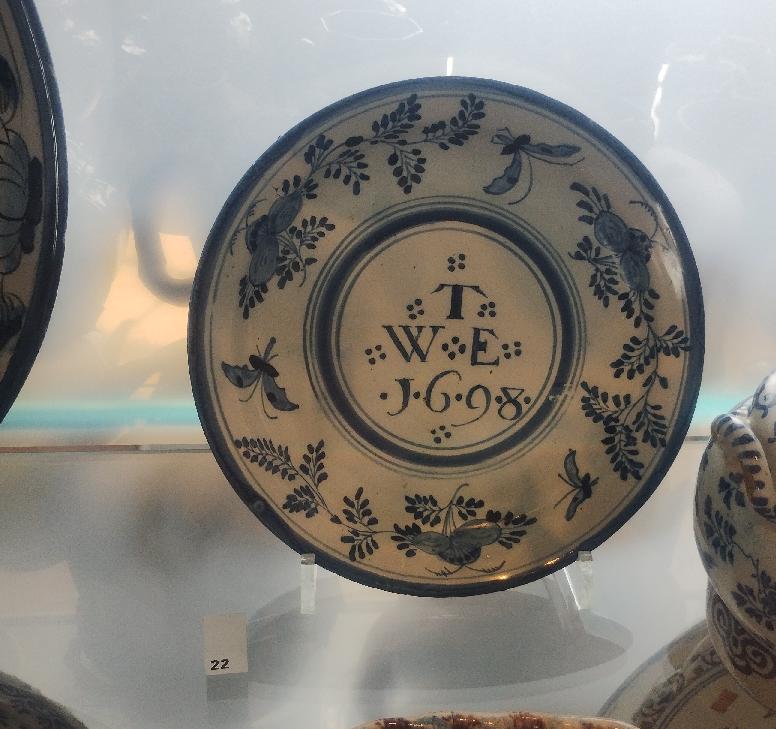

I’d like to finish with a little shout out to this very modest piece of work which I found on the fourth floor.

This little plate, dated 1698 is of course ridiculously old. I believe it’s Delftware, tin glazed and the V&A believe it to have been made in England. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a tin glazed plate as old as this in such good condition. Tin glazing seems to be terribly prone to chipping. Even museum pieces usually have a rim of nibbles around the edges. I think this example has had some restoration, but its displayed condition is remarkable.

It’s the sort of little gem that is worth looking out for in amongst the big, bright pieces that are the obvious eye-catchers that make a visit to the V&A so worthwhile.